Born in Pennsylvania’s West Nantmeal Township on April 10, 1822, George Lippard spent his childhood and adolescence in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. It was also in Philadelphia that he would die of tuberculosis at the tragically young age of 31. The brief life he lived was a remarkable one, filled with bestselling books and a relentless quest for social justice. He befriended another writer in Philadelphia who was struggling to make his name - Edgar Allan Poe. Lippard wrote of Poe soon after meeting him in 1842:

“He is, perhaps, the most original writer that ever existed in America. Delighting in the wild and visionary, his mind penetrates the inmost recesses of the human soul, creating vast and magnificent dreams, eloquent fancies, and terrible mysteries.”

Just seven years later, on July 12, 1849, an impoverished and unstable Poe went to George Lippard’s newspaper office begging for help. Lippard recalled Poe’s anguished words to him: “You are my last hope. If you fail me, I can do nothing but die.” Philadelphia was in the midst of a cholera epidemic at the time, but Lippard took to the streets to solicit money from other friends to aid Poe in his distress. After leaving Philadelphia for the last time on July 14, Poe wrote in a letter that he was “indebted for more than life” to Lippard. Poe went on to Richmond, then Baltimore, where he died on October 7, 1849, only 40 years old. While many contemporaries and critics decried Edgar Allan Poe as an insane alcoholic upon his death, George Lippard eulogized his departed friend as a genius:

“As an author, his name will live, while three-fourths of the bastard critics and mongrel authors of the present day go down to nothingness and night.”

An illustration of George Lippard in his youth.

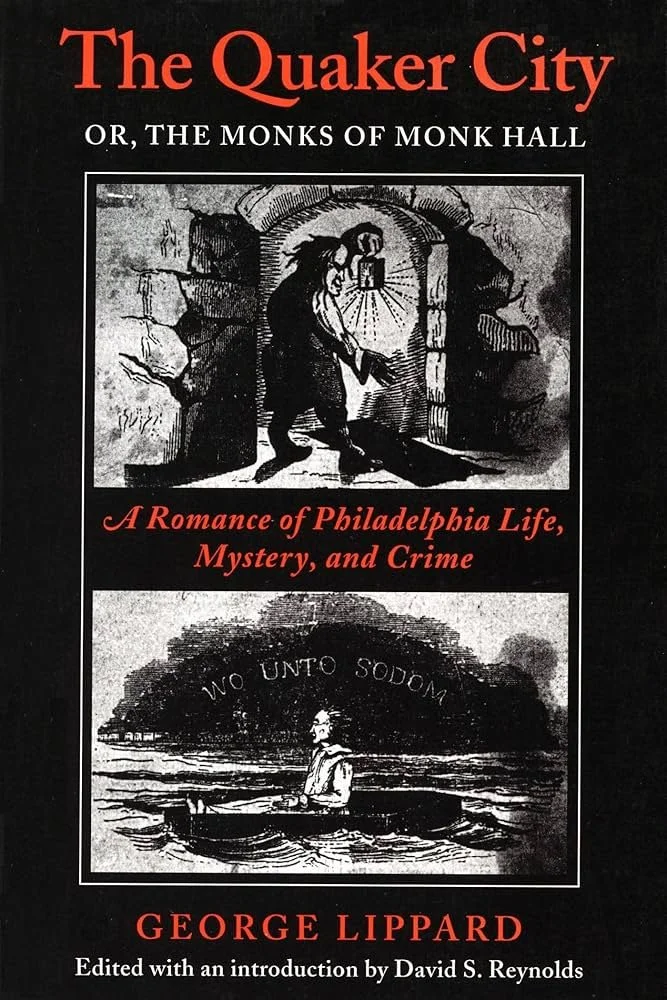

Lippard’s words would prove to be prophetic. Edgar Allan Poe is now unquestionably one of the most famous and beloved writers in American history. But what of George Lippard himself? He has been mostly forgotten, mainly remembered as a footnote in Poe’s life story. His works went out of print, the public moved on. Yet, in his lifetime George Lippard was wildly successful - his 1845 book The Quaker City or The Monks of Monk Hall became the first bestselling novel in American history with 60,000 copies sold in its first year of publication alone. He earned up to $4,000 dollars a year, an astonishing sum for a writer (the equivalent of $169,000 today). In 1848, the hugely influential Philadelphia magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book said of Lippard:

“This author has struck out on an entirely new path, and stands isolated on a point inaccessible to the mass of writers of the present day. He is unquestionably the most popular writer of the day, and his books are sold, edition after edition, thousand after thousand, while those of others accumulate, like useless lumber, on the shelves of the publishers.”

He was also famous for his romances and historical fiction, which many people came to regard as fact. The most well-known of these is a story in his 1847 book Washington and His Generals or Legends of the Revolution called “The Fourth of July, 1776” (also known as “Ring, Grandfather, Ring”) in which a mysterious stranger appears before the debating Second Continental Congress urging them to sign the Declaration of Independence, starting the still widely believed myth that the Liberty Bell was rung on July 4th to announce American Independence. Lippard’s fiction was so convincing that even President Ronald Reagan referenced it in a speech as a factual event. Future American literary giant Mark Twain, working briefly for the Philadelphia Inquirer as a young man in 1853, also fell under the spell of George Lippard’s words, writing in a letter:

“Unlike New York, I like this Philadelphia amazingly, and the people in it…I saw small steamboats, with their signs up--'For Wissahickon and Manayunk 25 cents.' George Lippard, in his Legends of Washington and his Generals, has rendered the Wissahickon sacred in my eyes, and I shall make that trip, as well as one to Germantown, soon.”

George Lippard had first considered becoming a Methodist minister, but abandoned that path due to the “contradiction between theory and practice” he perceived in the Christian church. His next move was to study to become a lawyer, but that too did not mesh with his belief in social justice. Lippard was frequently ill as he matured into adulthood, and seemed haunted by death - between 1830 and 1843 his mother, his brother, two of his sisters, and his father, would all die. His father’s death also brought the news that he was to receive no inheritance. For a time he wandered the streets of Philadelphia in an impoverished, bohemian existence, frequently unhoused, but always watching and learning about human nature. George Lippard wrote that his brief time working in law had exposed him to “social life, hidden sins, and iniquities covered with the cloak of authority.” His time on the streets during the Depression of 1837-1844 gave him deep insight into the hard, squalid lives of the working class and the poor. This inspired him to become a writer - and to use his words to expose the truth as he saw it. Author and scholar David S. Reynolds, in his introduction to the 1995 reprinting of The Quaker City by the University of Massachusetts Press, said:

“Between 1842 and 1852 he produced an average of a million words annually in novels, essays, and lectures. He was a literary volcano constantly erupting with hot rage against America’s ruling class…In a day when Thoreau’s social criticism went virtually unnoticed, Lippard’s took the nation by storm…The Quaker City stands out for its demonic energy, its soaring imaginativeness, and its revolutionary political themes.”

The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monk Hall, was George Lippard’s masterpiece and calling card, exposing the hypocrisy of high society and American capitalism as an insidious corrupter of human souls. It was also inspired by a true story of seduction and scandal that occurred in 1843 - the murder of Mahlon Hutchinson Heberton committed by Singleton Mercer. It was alleged that Heberton led Mercer’s sixteen year old sister Sarah to a brothel and raped her at gunpoint. After learning what had happened, Mercer shot and killed Heberton, and went on trial for murder. These events rocked Philadelphia high society to its core. Singleton Mercer argued that he was not guilty by reason of insanity, just two months after Edgar Allan Poe published his short story “The Tell-Tale Heart,” inspired by similar cases. After less than an hour of deliberation, the jury acquitted Mercer. Lippard used this lurid tale as the basis for the main plot of The Quaker City, in which one of its characters says:

“Philadelphia is not so pure as it looks…Alas, alas, I should have to say it…Whenever I behold its regular streets and formal look, I think of the whited sepulcher, without [on the outside] all purity, within, all rottenness and dead men’s bones.”

Like Charles Dickens, another writer with a social conscience and a keen eye for human nature, George Lippard first serialized his novel in newspapers. After only ten installments had been printed, it caused a sensation, so much so that ads began to appear around Philadelphia selling “Monk Hall Cigars, direct from Monk Hall.” Like many novels to come that are based on thinly disguised real events and people, the citizens of the city - high class and low - became obsessed with guessing who the book’s characters were meant to depict.

To further capitalize on the huge success of The Quaker City, Lippard wrote a play adaptation of it that was scheduled to be performed at the Chestnut Street Theatre in November 1844. Singleton Mercer, unhappy with his depiction, defaced the play’s poster outside the theater while a giant crowd watched, and bought two hundred tickets to the opening night “for the purpose of a grand row.” Rumors flew that the theater was going to be burned down during the performance. The Mayor of Philadelphia got involved, and the play was cancelled. After the cancellation was announced, an angry mob gathered outside of the theater - not out of outrage at the story’s content, but because they wanted to see the play! George Lippard, armed with a gun and a cane that concealed a sword, gave a speech to calm down the crowd. Sadly, his script for the play has yet to surface.

Lippard used his newfound fame for good: he started his own weekly newspaper, also named The Quaker City, in 1848, describing it as “a popular journal devoted to such matters of literature and news as will interest the great mass of readers.” This was the newspaper office in which Edgar Allan Poe appealed to Lippard for help before his untimely death. In 1850, he founded the Brotherhood of the Union - later known as the Brotherhood of America - an organization devoted to eliminating poverty and crime by raising awareness of and attacking the social issues that caused them. With its motto of “Truth, Hope, and Love,” the Brotherhood reached a peak membership of 30,000 by 1917, and was dissolved in 1994 after 144 years of existence.

On May 14, 1847, George Lippard married Rose Newman. The ceremony was an unusual one, perfectly in keeping with his love of the unconventional. Instead of a traditional wedding during the day in a church, Rose and George were married on a moonlit night on top of Mom Rinker’s Rock in what is now known today as Wissahickon Valley Park. The newlyweds then moved into a house (since demolished) at 965 North Sixth Street in Philadelphia, which was also Poe’s last residence in the city before he moved to New York. In 1850, Rose Newman Lippard gave birth to their daughter, who sadly died when she was only eighteen months old. A son was born in early 1851, but died in March of that year. And on May 21, 1851, George’s wife Rose Newman Lippard also died. In the midst of his immense grief, Lippard also recognized that his tuberculosis symptoms were getting worse, and he predicted in June 1853 (correctly) that he would not live much longer. With all the death of loved ones he endured, it is no surprise that he became a devotee of the Spiritualism movement, once stopping a lecture to say: “There is a figure in a shroud there! It is always behind me.”

Yet, he never stopped working and writing. He said that “a literature that does not work practically for the advancement of social reform, or which is too good or too dignified to picture the wrongs of the great mass of humanity, is just good for nothing at all.”

The last work that George Lippard ever wrote was a long article viciously critiquing the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. When his doctor told him he was too ill to write anymore, Lippard sketched twenty stories in the form of pictures. On February 9, 1854, he was still at his writing desk - and died early in the morning of February 10th just a month before he would have had his 32nd birthday. He was buried in Odd Fellow’s Cemetery at 24th and Diamond Streets in Philadelphia, but his remains, along with many others, were later reinterred at Lawnview Memorial Park in Rockledge, Pennsylvania in 1951. His gravestone was paid for by the Brotherhood of the Union, the organization Lippard had founded in 1850.

Upon the death of George Lippard, many in the press eulogized him and the work he did in his too brief life. The Philadelphia Public Ledger wrote that Lippard was:

“One of the shining lights in the firmament of the nineteenth century - one whose mind and pen has given the initiative to future stateswomen and men to remove the degradation and subserviency of labor to capital that now oppresses the human race…His memory will live, his genius will live, and future ages will recognize his works while here as a bright and good inheritance.”