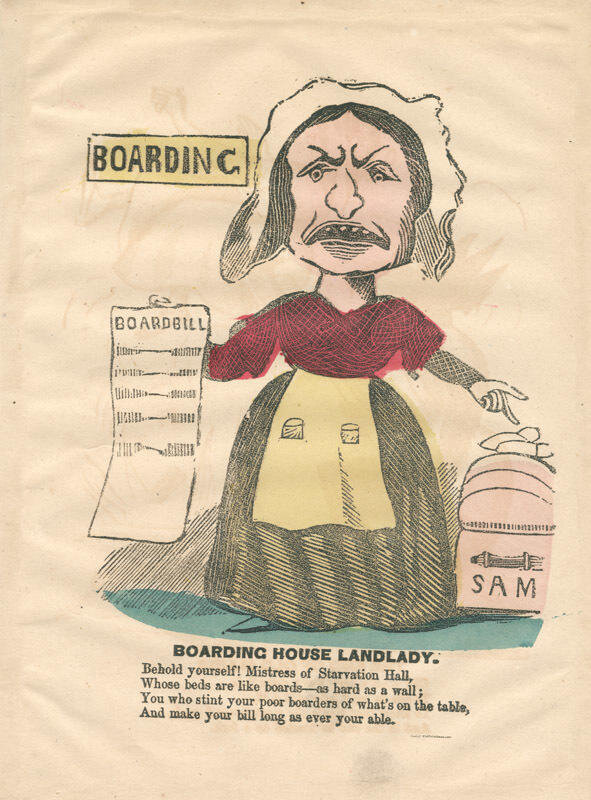

A nasty caricature of a landlady from the mid-to-late 18th century. Depictions of boarding houses as locations of immorality and their proprietors as greedy were symptoms of the public discourse about these places that emerged along with the idealized concept of the domestic sphere. Image from the collections of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

This week we are talking about boarding houses, and we got to interview Dr. Wendy Gamber, who is one of the leading scholars on the history of the American boarding house. We trace Elfreth’s Alley’s history of boarding houses through the 18th and 19th centuries to the era when, nationally, the institution came under fire through messaging like the image above. Yet even when the boarding house seemed to fade into the sands of time, we see emerging echoes of it in the 21st century.

Thanks to Dr. Wendy Gamber for taking the time to chat about the history of boarding houses. Look for her books, The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth-Century America and The Notorious Mrs. Clem: Murder and Money in the Gilded Age at your neighborhood independent book store.

Thanks to Nikia Boyer for talking with us about the Affordable Housing: Philadelphia Facebook group. If you’re ever looking for housing or to rent at an affordable rate, check them out.

SPONSORS

Our lead sponsor is Linode. Linode is the largest independent open cloud provider in the world, and its Headquarters is located just around the corner from Elfreth’s Alley on the Northeast corner of 3rd and Arch Streets, right next to the Betsy Ross House Museum. The tech company moved into the former Corn Exchange Building in 2018 and employees have relished the juxtaposition of old and new: Outside, concealed LEDs light up the historic facade, inside are flexible server rooms but also a library with a sliding ladder, and a former bank vault is now a conference room. Linode is committed to a culture that creates a sense of inclusion and belonging and is always looking for new team members. Learn more about job opportunities at linode.com/careers.

This episode is supported by Beyond the Bell Tours, Philadelphia's #1-rated tour company. Listeners of The Alley Cast may be interested in Beyond the Bell's 'Badass Women's History Tour,' which introduces audiences to cool colonial women, change makers, women in medicine, and more pioneers who have made their mark on this city of brother love and sisterly affection. Learn about the ways in which women, such as Hannah Callowhill Penn, Ona Judge, Barbara Gittings and more, have influenced and formed the city of Philadelphia. Uncover the incredible entrepreneurs, doctors, politicians, artists and activists that have made the city what it is today. Check out BeyondTheBellTours.com to find more information about this tour and others and to book your tour today.

This season is also sponsored by the History Department and the Center for Public History at Temple University. Many of the people who have worked on this podcast over the past two years have been alumni or graduate students at Temple University. A special thanks to Dr. Hilary Iris Lowe and the students in her “Managing History” course during the Fall of 2020 who did preliminary research and scriptwork for several episodes this season. Learn more about the department at www.cla.temple.edu/history/ and the Center at sites.temple.edu/centerforpublichistory/

SOURCES:

City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser, September 22, 1826

Fretz, Franklin Kline. “The Furnished Room Problem In Philadelphia.” Internet Archive. University of California Libraries, 1912. https://archive.org/details/furnishedroompro00fretrich/page/n9/mode/2up.

Gamber, Wendy. “Boarding and Lodging Houses.” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Rutgers University, 2017. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/boarding-and-lodging-houses/.

Gamber, Wendy. The Boarding House in Nineteenth-Century America. Baltimore (Md.): The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Gunn, Thomas Butler. The Physiology of New York Boarding-Houses. ProQuest . Whitefish, MT: Literary Licensing, 2014. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/templeuniv-ebooks/reader.action?docID=409980.

Igo, Sarah E. The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020.

“Local Items,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 8, 1849

“Philadelphia City Directories, 1794-1808.” Internet Archive, Philadelphia Museum of Art, n.d. https://archive.org/search.php?query=philadelphia+city+directory+1793.

Sivitz, Paul, and Billy Smith, ““ Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/philadelphia-and-its-people-in-maps-the-1790s/

Wright, R. R., compiler, with Ernest Smith, The Philadelphia colored directory: a handbook of the religious, social, political, professional, business and other activities of the Negroes of Philadelphia. 1907: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006040566

Wulf, Karin. Not All Wives. JSTOR. Cornell University Press, 2000. https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.temple.edu/stable/10.7591/j.ctvr7fbd4.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Ted Maust: In September, 1826, a well-dressed man arrived at a boarding house on Elfreth’s Alley, inquiring whether they had space for him. He was assured there was, and he agreed to return with his luggage. He came back later, accompanied by a Black porter, who carried a shiny new leather bag, and settled into his new lodgings. When he left the house shortly after, the well-dressed lodger was carrying a bundle of something, but no one thought anything of it. When dinnertime came, and the man was called to join the meal, he was nowhere to be found. An inventory was taken and it was discovered that he had taken along with him the most valuable contents from the trunks of two permanent boarders. When they opened the new leather bag he had brought, they found that it was full of nothing but old sail cloth.

Welcome to the Alley Cast, a podcast from the Elfreth’s Alley Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We trace the stories of people who worked, lived, and encountered this special street for over 300 years. While the stories we tell often center on Elfreth’s Alley and the surrounding Old City neighborhood, we also explore threads which take us across the city and around the globe.

In this episode we will be discussing the boarding house and both the people who ran these establishments and the people who stayed in them. Elfreth’s Alley had a long history of boarding from the late 18th century through much of the 19th century, a history largely of women and immigrants in the City of Homes.

In Season 1 of this podcast, we highlighted a lot of women on Elfreth’s Alley who headed households, who ran businesses, and who generally challenge our understanding of the experiences of early American women. Yet even for those women, keeping a home was not only a basic expectation, but an arduous and never-ending task. Laundry alone was extremely time-consuming and physically exhausting. In episode 4 of Season 1 we talked about how Margaret, who lived in house 130, and others like her, entered the marketplace, receiving wages for their expertise at domestic tasks. The people who took in boarders did the same, monetizing their homes and the work they did to maintain them.

The census records of homes on Elfreth’s Alley, from the first census in 1790 to the most recent publicly available one, in 1940, show that the taking in boarders was a very common practice on the street, as it was in the surrounding city. In the 1790s, 1 in 8 households in Philadelphia was headed by a woman, and of those, a significant portion ran boarding houses. In the 19th century, historians estimate that one in four houses in Philadelphia took in boarders.

Hosting boarders took various forms. Apprentices and journeymen often received shelter and food within the household of their boss in return for their work.

Boarding might also helped households make it through tough economic times. For instance, in the years after dressmaker Sarah Melton’s death in 1794, Elizabeth Carr, who had inherited house #126 and the dressmaking business from her, rented part of the house to Benjamin Lodor, who, along with his brother John, was building--or having built--two houses across the street at #129 and #131. Lodor’s rent likely supplemented Carr’s business income as she coped with the loss of Melton.

Then there were houses where the majority of residents were boarders. These are what we will call boarding houses, though the distinction between a boarding house and a house with boarders was not always clear, not least because there were periods where boarding houses, especially those associated with lower-income clientele, were seen as disreputable. I talked with Dr. Wendy Gamber, author of The Boarding House in Nineteenth-Century America about this:

Dr. Wendy Gamber: But I did have a wonderful Boston diary from a woman named Susan Brown Forbes. Who wrote in her diary, and I knew that she was taking in borders. She's one of these people who kept a diary for years and years and years. And she said, One day, I think was in 1863 “Oh, I, I placed an ad in the transcript this morning.” And so I went to the Boston Transcript and found her add in she's she was advertising, boarding and lodging in a private family. Well, I knew from city directories from her diary from the census that her quote unquote, private family at any one time contains seven to 10 unrelated people, and then I'd find census entries from Irish women who kept you know, maybe two or three people boarders and who were described, but either they self described, or the census taker described them as keeping boarding houses. So I realized very quickly that that notion, the difference between a private family and keeping a boarding house was a semantic one, intended to denote class.

Dr. Gamber’s book draws on a wealth of diaries and correspondence, among other sources, to portray the boarding house experience. I asked her who was typically running boarding houses:

Gamber: So I found that a variety of women ran boarding houses, and some of them were widows, which would have been perhaps very common, some were single, and many were married. And even when they were when married couples ran a boarding house, the husband was relatively absent. He tended not to dine with the boarders, as did the landlady. And so it really was women's work. And I would say, you know, it remained that way. And even if you look at Airbnb, [well, which is now collapsed, but I looked at some of the stats for Airbnb, I believe it was last year.] An astonishing proportion of the people who have places on Airbnb and who run those concerns are women. So it's very much quote unquote, housekeeping commercialized.

But of course the host was only one part of the boarding house equation--there were also the boarders themselves:

Gamber: With middle class boarding houses, the typical composition in the 19th century would have been mostly young men who worked in clerical occupations, clerical occupations, until the very late 19th and early 20th centuries were primarily male occupations. So young men who worked downtown in downtowns as clerks, perhaps a single woman or two, and a few married couples. And, and I think part of that constellation was to maintain respectability: as long as you show that your establishment was a respectable one, and that people were behaving themselves, it was actually important to have a little bit of heterosexuality in that particular domicile. I think many working class boarding houses probably housed more men. But, but I think women were never absent.

Gamber: they tended to have a kind of long term core of people who boarded there for several years, and then a lot of short term turnover. And those, those long term core borders do seem to have developed, you know, not necessarily romantic relationships, but an attachment to their boarding houses, to their fellow borders whom stayed for similar amounts of time and into their landladies and one, one account I do have, I'll go back to Susan, Susan Forbes, because her diary runs on forever. So she, as I said, was initially a boarder. And, and she actually met her husband at the boarding house, he was a clerk, Alexander Ford's Forbes. She called him Sandy. He was Scottish. And, and a bunch of his co workers, who were also clerks in downtown Boston, boarded at this boarding house. And so when they get married, and start their own boarding house, a lot of these guys, you know, move with them. And at one point, she has--it's very cryptic, but she has a dispute with a couple of these guys, it's it seems that maybe they didn't get up on time for breakfast, and then, you know, expected her to prepare another breakfast or something, they get miffed and they go to another boarding house, and she just has this little breakdown. I mean, she was always having, you know, sick headaches and heart palpitations and such. She probably really did, but she just had this. She was very upset that they left you know, she's so she had this kind of maternal relationship with them. And they eventually come back. And and she's happy.

The interactions of people within a boarding house were complex! At times they acted like a family, other times as strangers sharing a house. I asked Dr. Gamber how hosts and boarders might find ways to share the space:

Gamber: I think, boarding houses while they were not, quote unquote, private in the sense that they housed people who are not members of the immediate family also found ways to enact those boundaries. So for example, the the parlor in a boarding house, as in a home would be public space, and a good respectable landlady would keep an eye on what was happening in the parlor, because parlor was the place where young couples would would court. Of course, you know, sitting, being socially distanced a different manner than we think of it today and not engaging in anything untoward. On the other hand, because at least a middle class boarding house, in many ways, did approximate a kind of family. And some people referred. Susan Forbes, for example, before she ran her own boarding house was a border, and she at 34 Oxford Street in Boston. And she would always refer to “our family at 34”. And so these in boarding houses, people often behaved as if they were members of families, I have accounts of people going into each other's rooms without necessarily knocking, of boarders, funeral funerals of being held in the, in the parlor of the boarding house.

Gamber: I have a wonderful anecdote from an man named Richard Barker, who was a lawyer who, from Louisville, Kentucky, but who will whose business often took him to, to New York City, where for many months of the year, he would board and he writes of his room being separated only by a partition from the room next door, and in the room next door, a medium holds a seance, and he writes to his wife about, you know, overhearing this spirit of, I believe it was, you know, a Native American Chief, you know, come to, you know, materialize. So and he thinks this, you know, he, while there were things he complained about, he, you know, he thought this was funny, and it was not out of the realm of expectation

There was certainly vulnerability in these close quarters, and Dr. Gamber confirmed that boardinghouse theft, like the story we led off this episode with, did happen.

Gamber: a particular category of criminal, but they did take advantage of that sort of familial atmosphere and the fact that, you know, somebody could be sitting and sewing in the parlor chatting with another border, and you know, her door wouldn't be locked and, you know, the boarding house thief could make off with her her jewels or other possessions.

Boarding houses inhabitants in the early 19th century came from all walks of life, but individual boarding houses more often catered to lodgers from a single rung of the economic ladder. Some also became known for hosting immigrants from specific countries or regions.

For example, Margaret McNamara was born in 1840 in Ireland, and immigrated to The United States. In 1880 she is recorded as housing nine boarders in her home on Mifflin Street in South Philadelphia, all of them were also Irish immigrants.

Immigrants were not the only minority group of Philadelphia operating boarding houses however, Black Philadelphians also took part in boarding. Operating largely in the same capacity as immigrant boarding houses, Black boarding houses only housed other African Americans. There is evidence that some Black boarding houses in Philadelphia as well as Camden, New Jersey operated as informal stops on the Underground Railroad, providing shelter and food for escaped slaves.

I asked Dr. Gamber about the forces that led to the segregation of boarding houses.

Gamber: But certainly, both North and South, they were segregated by race. And for a long time, it was perfectly legal for boarding housekeepers to segregate and of course, even after it was illegal, they they still did. Certainly, one might find Black women or men as as servants, but not as boarders. So in Philadelphia, and other northern cities, You see, separate boarding houses for the, for African Americans, which were essential for anyone, any black person who was traveling, who would not be admitted to a white-managed hotel or or boarding house,

Gamber: but for the most part, segregation was rampant. I don't think, for example, middle class, Anglo American boarders would probably not, at least in the 19th century, admit Irish boarders, although they might employ Irish servants. And I think there are all kinds of very fine tuned distinctions that I could only begin to capture and about the different kinds of boarding houses, some people would describe them as, you know, first class, second class, third class and it's, most of that had to do some a lot of that had to do with the, the accommodations that could be offered and the quality of the food and, and the, you know, the, the bedding and the cleanliness and so on and so forth. But I think a lot of it had to do with perceptions of who the clientele was. So I would say that the color line was very, very clearly drawn. But there were all kinds of other ways in which discrimination operated and, and in which, you know, land ladies were really the gatekeepers.

Gamber: you could be kicked out for, for bad behavior, which might include, you know, being caught drinking alcohol, not necessarily that because you were, you know, gone out, you went on, you know, drunken spree and smashed furniture. But, you know, if you just if somebody said, Oh, you know, I saw this person at the bar, landlady could say, Hey, you know, you're out of here, you are threatening the respectability of my establishment.

Finding the right boarding house was probably a significant challenge for the prospective lodger, but especially for Black Americans. Beginning in 1907, Richard R. Wright, Junior, the first Black American to earn a PhD in Sociology, published the Philadelphia Colored Directory, subtitled “a handbook of the religious, social, political, professional, business and other activities of the Negroes of Philadelphia.” Through the early 1910s, this Directory lists a few boarding houses, clustered around a single block of Pine Street in between 12th and 13th streets. In the 1907 issue of Wright’s Directory, the Metropolitan Baptist Church advertised a “Bureau of Information Regarding Respectable Boarding Houses” at 20th and Tasker Streets to help the house-seeker on their way.

Despite the large number of boarding arrangements in Philadelphia, the records are relatively slim. The vast majority of boarding agreements were informal and didn't leave a paper trail. But there are some traces, such as newspaper stories like the one at the beginning of this episode. And from 1794 to the 1860s, Philadelphia city directories provide a breadcrumb trail showing a near-constant presence of boarding houses on Elfreth’s Alley. In some cases, the proprietor’s name is followed by the words “boarding house” in the directory entry, other times by the abbreviation “b h.” It’s possible that other women who appear in the directories without an occupation or other description were also operating boarding houses. We don’t know which boarding house was the target of the thieves in 1826, but we do know some things about the boarding houses on the street over the years.

Following national trends, many of the boarding house operators on the Alley were widows.

Ann Taylor’s husband, Enoch Taylor, and his brother Benjamin built two houses on the property that is now #116 in 1785. The Taylor brothers, both bricklayers, built one home in front of the other, the rear house accessed via a passageway from the street. When Yellow Fever visited Philadelphia in the 1790s, Enoch was one of the epidemic’s casualties. Ann, left with several sons to raise, began taking in boarders, appearing in directories and census records from 1795 to 1811.

While Ann Taylor owned her house, many boarding houses were operated out of rented homes. Catherine MacLeod appears in the Directories at #130 in 1793 and 1794 as “widow” before being listed as a “widow [comma] boarding house” from 1795 through 1798. MacLeod’s tenure at #130 bridged two owners of the house, which was sold in 1795. A decade later, Isabel McClane was also listed operating a boarding house at #130. The property included a secondary building on the lot and it seems likely that both women were operating out of that structure, which had a separate entrance, while the property owners lived in the main house.

Mary Hillman, at #128 Elfreth’s Alley, owned her house after the death of her husband, but sold the property at one point before later purchasing it back. Hillman was listed in some directories as a teacher or “tutress”--perhaps she changed career or perhaps she tutored in addition to her boarding house work.

After Mary Hillman died in 1847, Sarah Morss rented #128 from Hillman’s heirs before they sold the property a few years later. Morss operated a boarding house, just as Hillman had done before, for at least two years.

For property owners who couldn’t make full use of a property, renting to a woman to take in boarders was one way to make some money. Sarah Neill’s boarding house, listed in 1823 and 1824, was operated out of #135 Elfreth’s Alley, owned by John Angue. Angue had been a distiller but by 1823, he was nearing the end of his life and renting part of the house to Neill for her business probably provided him needed income after he stopped working.

Some boarding houses were adjacent to other businesses. A newspaper story from 1849 reports that a fire broke out in a green grocery run by a Mrs. Martin on the Northwest corner of Front Street and Elfreth’s Alley. In addition to the store, the building served as a “boarding establishment” for a “great number” of shoemakers. While the fire claimed the building, no one was injured.

While Ann Taylor ran a boarding house in the rear house of #116 for at least 16 years, most of these women operated boarding houses on a temporary basis. It is also possible that those who entered the written record for only a year or two in fact operated boarding houses longer, declining to advertise. Perhaps these entrepreneurs didn’t need to advertise, but it is also possible that they were keeping a low profile. As the nineteenth century progressed, the boarding house came under serious attack.

The real crux of Dr. Gamber’s book deals with the fact that the long-held practice of boarding became the target of criticism from the image of the family home, an ideal that was being created in the mid 19th century. Economic changes were leading to a sharper division between the spheres of work and home. Workers increasingly left the home to go to a factory, a marketplace, or an office for their jobs, and social commentary from writers such as Catharine Beecher imbued the home, now freed of labor with a host of new ideas.

Gamber: So because this idea of home because homes were supposed to be private boarding houses become the sort of the polar opposite and the the institution that everybody, or at least middle class commentators who want to uphold this ideal Can, can berate and denigrate.

The labor that remained in the home--cooking, cleaning, childcare--became a default component of this idealized private home, rather than labor seen as marketable. This changing perception sometimes led to conflict between boarders and their hosts.

Gamber: you get all these complaints from from borders, about how awful the conditions are, how awful The food is. And it's not because hey, I can't afford to pay higher rent, it's because this mean landlady is stingy. And she's profiting from my, from the board that I that I pay. So in so what's interesting is that borders want to think that they're getting the comforts of home, they don't want to pay for them.

The criticisms leveled at the American boarding house also played up the association of these homes with immigrants, Black Americans, and lower class citizens. This was a self-fulfilling prophecy--as the boarding house became seen as unseemly, many middle and upper class boarding houses closed or essentially rebranded, leaving a larger share of boarding houses associated with people at the fringes of society. And by the late 1800s, boarding houses began to evolve into lodging houses.

Lodging houses, also called furnished rooms, differed from boarding houses in a few key ways. First, boarding houses were primarily for long-term tenants, rarely renting to people who would only be around for a few days at a time. Furnished rooms changed this dynamic, creating a space where owners could open their doors for limited amounts of time. As a consequence, roomers would find food outside of their lodgings, increasing the comings and goings of tenants.

Dr. Gamber suggests that this period also brought changes in the type of people who used boarding houses.

Gamber: I think by the early 20th century [and into the 20th century,] when boarding houses, by and large, morph into what were called lodging houses where you no longer got your meals, where your landlady no longer provided housekeeping services, where you simply rented a room were much more much more catered to young, single people, both men and women. And they become increasingly disreputable. And part of this is because of the rise of apartments, which respectable middle class people repaired to so that lodging houses or rooming houses or furnished room room houses, as they were sometimes called, become the residences of people who are less affluent.

Due to the coming and going nature of the furnished rooms, they allegedly caused an increase in transience and vice in the areas they occupied, as well as created economic problems left to be solved by the city of Philadelphia. In his dissertation published in 1912, Franklin Fretz claims the link between boarding houses and furnished rooms is strong, and that many transitioned from one to the other. Fretz is so concerned about the influx of furnished rooms and the problems they allegedly exacerbate that he titled his dissertation, “The Furnished Room Problem in Philadelphia.” He would not be the only person to become alarmist over this shift.

Despite the distinctions that still existed between some boarding houses and the furnished room houses, Philadelphians often conflated the two and the furnished rooms would create even more uproar in Philadelphia, and lead to a shift in rhetoric about Philadelphia itself. By the late 1800s and into the turn of the century the city began to rebrand itself as “The City of Homes” in an attempt to distance itself from the growing furnished room industry. Yet as the furnished room house largely replaced the boarding house, the changing times led to historic amnesia and former critics began praising boarding houses for their role in upholding the traditional home. This change in rhetoric comes from an attempt to conquer the beast that was furnished rooms.

The shift away from boarding houses can be seen on Elfreth’s Alley. After 1900, while many households listed a single boarder or lodger on the census, few, if any, houses could be described as boarding houses.

A dozen or so households in the first 4 decades of the 20th century listed two boarders or lodgers on the census, with only a few listing three. Perhaps the closest thing to the 18th- or 19th-century boarding house was the household of Mary Krause in 1930. Krause was an Irish immigrant, though her last name suggests perhaps she married a man of German descent. By 1930, she was 65 and widowed, living in the front house of #116, on the same lot where Ann Taylor had made her home and living a century before. Krause lived with two of her grandsons, who were in their 20s, and three boarders. Two of the boarders were Mary Fearon, herself a second-generation Irish-American and a widow, and her 18-year old son Thomas. The third was Arthur Muller, a 75-year old German-American widower. It is possible this household was simply a blended household, negotiating terms of cohabitation in order to secure shelter for each member of the household, or perhaps it was a throwback to the boarding house of old. It is impossible to know, in large part because the census didn’t provide detail on the relationships in the household beyond the people related to the head of the household.

The lodging house still existed beyond the limits of the Alley--in 1910, a house nearby listed one proprietor and 23 lodgers--but it wouldn’t be long until other housing options largely replaced lodging houses.

Ultimately, there were a wide variety of replacements or substitutes for the American boarding house. As Dr. Gamber said earlier, the rise of apartments fulfilled much of the demand that had previously been met by boarding houses.

The options for temporary housing for visitors or newcomers have also evolved since the heyday of the boarding house. Hotels became more common and accessible, as did more affordable beds at the YMCA or youth hostels. The Green Books of the 1940s through the 1960s listed “Tourist Rooms” in Germantown, and one of the clearest current descendants of the boarding house is vacation rentals such as AirBnB and Vrbo. These apps allow homeowners to rent out properties or rooms to visitors, and often include complimentary snacks or breakfast foods in addition to lodging. Several homes on Elfreth’s Alley have used AirBnB in the recent past, allowing visitors to this historic street to make it their home, if only for a night or two. Interestingly, at least a couple of these properties which have been listed on AirBnB have a history as boarding houses!

In addition to meeting the needs of travelers, boarding houses also served a need for cheap housing, especially for newcomers to the city. Now that boarding houses are mostly a thing of the past here in Philadelphia, who or what is fulfilling that need? In my experience, lots of young people still live communally, with roommates who may be good friends or new acquaintances. And one of the best places to find those kinds of living situations is a Facebook group called “Affordable Housing: Philadelphia.” I talked with Nikia Boyer, who serves as a volunteer admin, about how the group works.

Nikia Boyer :Our mission is to advertise as much affordable housing in Philadelphia as we can, we do have income limits for per room for a single room, our group limit is $650. And for anything above that, it's about $600. A room. So two bedrooms is 1200, 3 bedrooms is at least 1800, and so on. We are restricted to apartments within the Philadelphia city limits. And we just encourage each other to be kind to each other in our search.

Boyer: Well, most of the people that come in our group are students, we had a lot of Penn and Drexel students who are looking for housing or Temple. Now, a lot of Temple students get a lot of Temple landlords advertising housing, and those places go pretty fast. We also get people who are lately we get people now who have been displaced because of because the pandemic, they're coming from New Jersey and New York, and they're looking for someplace that is within their budget, you know, a lot of people are moving back to Philadelphia from outside, and they're looking for, you know, to move it back after they've moved from Jersey, and I'm looking for a place that's within their budget. My only sadness is that mostly we have a lot of rooms and a lot of sharing and not very much of individual apartments so much. And most of our apartments come from basically a few areas of the city and not all over. I don't think our group is that well known, like in places like Mount Airy, and you know, the far northeast and things like that. And I wish that we would get more people from that area. So we have more of a representation. Right now. We're mostly West Philly, and temple and some places in the northeast. So it's it's scattered, but it's not as inclusive as I would personally like.

I asked Boyer who posts ads to the group.

Boyer: I'd say it's probably 70% roommates and 30%. Landlords. [Okay. And, yeah, a lot] of the posts that we approve, I will say 70% 7030. There are a lot of landlords that seem to not read the the instructions and post a lot of a lot of apartments that are just way outside the price range a lot, a lot. So the people approve that 7030 but I have to say if it was, you know, landlords plus a 6040.

And just like the boarding house thieves of yesteryear, there are those who will prey on people desperate for housing. Boyer and her fellow mods take pains to keep scammers out of their community and to warn about the risk of scams:

Boyer: we had to police the group very tightly for comments, because a lot of people a lot of scammers will sneak in. And they'll post comments about, well, if you're interested in rent to own click here on this Google site, or, you know, then lately, they'll start to post and edit comments later, you know, offering more scams. And a couple people have posted that I needed apartment quickly because I lost my money to a scam, it does happen fairly often.

I asked Boyer about the challenge facing someone in Philadelphia looking for housing on a budget.

Boyer: You know, so it's, it's very stressful. And then it's, you know, not everything posted to one place that you have saved it is one place sift through the scams Do you know this person, you can handle this person or maybe you know, someone has a hookup, you know, it's very stressful, it's even more stressful if you have like, you know, children or a dog or something like that, because a lot of our rooms, you know, people do not want children. They don't like couples and they don't want dogs. So it's, it's really it's, it's really hard. It's getting harder every year.

And of course, this past year has brought new challenges

Boyer: Well, we have three questions that we ask people to answer before they come into our group. And those questions are pretty enlightening. We ask people you know, why are you using the Affordable housing, Philadelphia, why do you like Philadelphia, and a lot of people say because they pandemic, I have to, you know, move out of my place or, you know, I just had I just got a new job or I lost my job, there are a lot of people who have lost their job and, you know, moving back or moving out and trying to find, you know, something to put together from multiple part time jobs, you know, they have someone helping them out. It's, you know, it's, it's really enlightening. And I read every, every application, I read every answer. And it's, it's been really eye opening about, you know, the struggle that people are going through. Yes, not easy for anybody. But they're still, you know, students, you know, looking for places, they're still, you know, they're still always people looking for looking for places. So we're here.

In its few years of existence, the Affordable Housing group has helped many, many people find housing in this city, but Boyer hopes that it can grow even further.

Boyer: I really would like, you know, more landlords of color, and to come an offer apartments in other neighborhoods, besides going to just West Philly, South Philly, seriously, in the northeast, I would like people of all neighborhoods to come and offer more places. But we don't advertise that I would like to get the word out.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, boarding houses answered a need. Dr. Wendy Gamber put it simply--

Gamber: boarding and taking in borders, or at least, you know, by other names, is a is a way for people to get by both people who own or rent houses that they are, or apartments that they don't want to be evicted from, and people who need a place to stay.

The arrangement between lodger and host took a variety of forms and resulted in a broad variety of relationships and experiences, characterized by vulnerability and trust, and constant negotiation of personal and communal space. People from all walks of life participated in these relationships, until they didn’t. In the mid 19th century, the boarding house became a foil for the ideal of American domesticity, and evolved as a result. Even the lodging rooms, considered blights on neighborhoods by would-be reformers, met a need, however. And there are still relationships and institutions in which we can recognize the echo of the boarding house, from roommates found on Facebook to AirBnBs.

And after all of this, the boarding house may not be entirely a thing of the past. Dr. Gamber mentioned that during the Great Recession, there was a rise, once again, of people advertising rooms in their home for rent as a way to pay the bills. Whether this trend continues in a post-COVID world is yet to be seen.

Credits

History is a group effort! This episode was researched and written by Lauren Kennedy and Ted Maust, with creative input from Margaret Sanford and Enya Xiang, and the Managing History Class in Fall 2020.

Thanks again to our sponsors Linode, the History Department of Temple University, and Beyond the Bell Tours. Support is also provided by the Philadelphia Cultural Fund and the Museum Council of Greater Philadelphia.

A transcript of this episode with sources is available on the episode page at ElfrethsAlley.org/TheAlleyCast and the link in the show notes.

The songs used in this episode are “Open Flames” and “An Oddly Formal Dance,” both by Blue Dot Sessions, both used under Creative Commons license.

This podcast is recorded on the unceded indigenous territory of the Lenni-Lenape people, who were and continue to be active stewards of the land. We recognize that words are not enough and we aim to actively uphold indigenous visibility and sovereignty for individuals and communities who live here now, and for those who were forcibly removed from their Homelands. By offering this Land Acknowledgment, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the Elfreth’s Alley Museum accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Season 2 of The Alley Cast! Remember that one of the best ways you can support our work is by telling other people about this show and rating us on podcast apps such as Apple Podcasts.

You can sustain the work of the Elfreth’s Alley Museum by making a donation at elfrethsalley.org/donate or by joining our Patreon at patreon.com/elfrethsalley.